Women on average earn 18 per cent less than men per hour, according to a new study from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

The gap widens the most 12 years following the birth of a female employee’s first child, according to the report, suggesting that mothers are taken off the fast-track for raises and promotions. 12 years later, these employees earn 33 per cent less than their male counterparts.

The motherhood penalty

The IFS study shows that this maternity-related pay penalty is not because of reduced hourly pay, but by the increased likelihood for women with children working part-time.

The salaries of men and women working full-time pull further and further ahead, leaving part-time mothers in the lurch.

For women who take a hiatus from working after childbirth face a ‘penalty; their wages are two per cent lower for each year spent out of the workforce.

Before the first child is born, the employment rates of men and women are almost equal, although the pay gap still persists.

But between the year before and the year after the birth of the child, women’s employment rates drop by 33 percentage points for women, while barely changing for men.

The pay and promotion gap

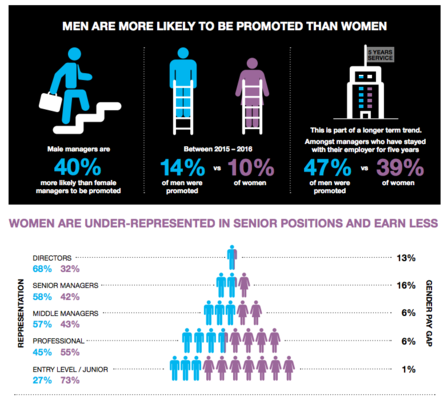

A study from the Chartered Management Institute (CMI) reveals men are 40 per cent more likely to get promoted into senior management roles. This is one of the main causes of the gender pay gap, which remains largely unchanged this year at 23.1 per cent compared to 22.8 per cent in 2015.

Analysis of salary data of more than 60,000 UK employees found that in the past year, 14 per cent of men in management roles were promoted into higher positions compared to 10 per cent of women.

Even allowing for staff turnover, men continue to be promoted ahead of women in management roles. The data reveal that for managers who have stayed with the same employer for the last five years, 47 per cent of men were promoted compared to 39 per cent of women.

Ann Francke, chief executive of CMI, says that the imminent pay reporting regulations will focus employers on closing the gender pay gap in their organisations.

“Promoting men ahead of women is keeping us all back. Diversity delivers better financial results, better culture and better decision making,” she says.

“Even before the new regulations kick in, employers need to get on board with reporting on their recruitment and promotion policies and how much they pay their men and women.

“Transparency and targets are what we need to deal with stubborn problems like the gender pay gap.”

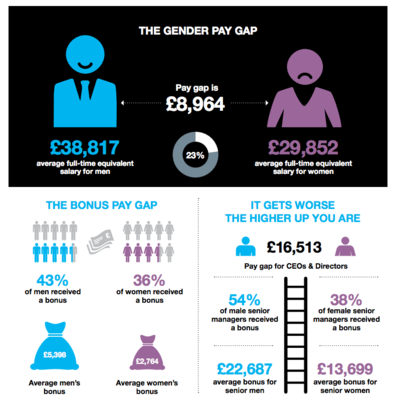

The average full-time equivalent salary for male managers now stands at £38,817, £8,964 more than the average female manager’s salary. The pay gap is even higher for directors and CEOs, with men £16,513 more than women at the same level.

A career bottleneck

The CMI study found fewer women in executive positions than men. While women comprise 73 per cent of the workforce in entry and junior level roles, female representation drops to 42 per cent at the level of senior management.

Why are there fewer women moving up? While the IFS study suggests the motherhood penalty, where employers and management work on assumptions around working mothers, Mark Crail, content director at CMI’s research partner XpertHR believes that the pay gap stems from a wider reluctance to promote women.

“The gender pay gap is not primarily about men and women being paid differently for doing the same job,” he asserts.

“It’s much more about men being present in greater numbers than women the higher up the organisation you go. Our research shows that this gap begins to open up at relatively junior levels and widens – primarily because men are more likely to be promoted.”

Mind the bonus gap

Men’s pay further outstrips that of women’s because of a ‘bonus gap’. In the past year, 43 per cent of men received an annual bonus compared to 36 per cent of women.

For more senior roles the gap grows, with 54 per cent of male senior managers receiving a bonus compared to 38 per cent females of the same level of seniority.

At this level, men command an average bonus of £22,687 compared to women’s £13,699.

This sets female employees back in terms of take-home pay, and since bonuses insidiously work on the assumption of merit, it may be taken for granted that women are as hardworking or worthy as men for promotions and pay rises.

The public sector as a role model

The public service sector has the overall lowest gender pay gap of 16 per cent compared to 23 per cent in the private sector.

In November 2015, the Government announced plans for new legislation to tackle the gender pay gap, including making it compulsory for large companies to report on how much they pay their male and female staff.

The regulations are due to come into effect in April 2017, but scaling the pay gap may take more than reporting.

Greater care needs to be given in terms of training, support and benefits, to factions of the workforce like working mothers and junior female employees, to prevent them from lagging behind because of baseless assumptions at a management level.

It’s a cultural shift that makes the most business sense.