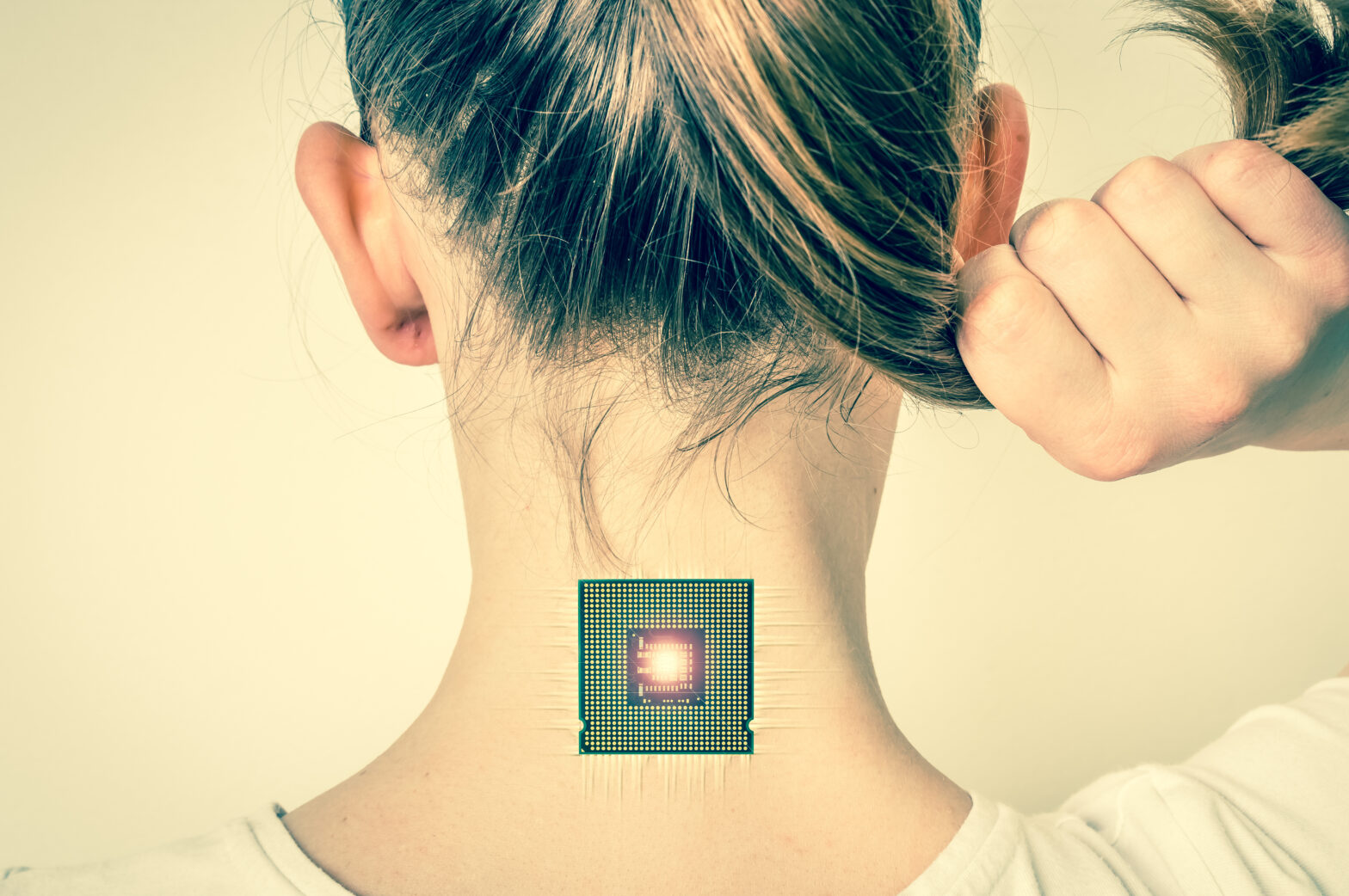

US software company Three Square Market (32M) recently announced that they were trading in work passes for RFID microchips on a trial basis. On our side of the pond, a new survey reveals that employees are highly unlikely to stick around if this were the case.

The research was commissioned by TalkTalk Business’ Workforces 2025 initiative, which examines the trends set to transform the future of employment and the workplace. Over 2,000 working adults over the age of 18 in the UK in June 2017 were asked to consider how they would react if their employer asked them to have a microchip implanted into their body to help increase their efficiency at work.

The smaller the business, the less likely employers are to consider implanting employees with electronic chips as a priority. Less than one in ten employers do, however, consider it a business priority over the next 10 years. Why? According to over a third of the employers surveyed, it was for streamlining employees’ access to work devices, but for one in five employers, it’s more for tracking employees’ movements.

Other findings from the research found that generationally speaking, over a third of Generation Z and younger millennials vehemently oppose wearing an RFID implant, citing they would quit their job. Older millennials (between 25 and 34) are more open to trialling the technology, however. Across the board, five per cent of British workers would consider wearing a microchip if they were paid extra.

“My immediate thought is, why would it need to be implanted?,” asks Stephen Robinson, employment partner at law firm Ward Hadaway. “The microchip is much like the fobs that hang around our necks or in our handbags. Even having access via phone would be more convenient than an implant.”

Convenience and common sense aside, is microchipping your staff legal? Robinson says it depends on employers asking individuals for consent, and more importantly, make sure that volunteering to be microchipped is an informed decision made by employees. Employers who are bought in will understandably explain the benefits of these implants, but Robinson stresses that they ought to also say explain the negatives.

“There are some technological advantages to the chip, but what happens if the individual is on probation and has to leave? How easy is it to be removed? What happens if it reacts badly to the individual’s skin or body? What happens if that individual decides not to have it anymore? How easy is it to remove it? There are practical issues like that,” he says.

Another element to this argument is the question of employee privacy. Employers need to stress that the chips won’t be used as monitoring devices. “This is where it’s a little bit like the Twilight Zone, where concerns that Big Brother is watching you begins. This is also where the law becomes quite protective over the individual’s privacy.”

The fact that the impetus stems from a business need raises a lot more questions.

“Because this comes from a business need, it’s really interesting, and we see negatives in it. In the next few years, big manufacturers like Apple or Samsung may introduce something similar, but because the technology will be led by safe leaders in the industry, it will be marketed much better and become part of the norm. Then it’ll be easier for people (and businesses) to embrace the technology,” Robinson explains.

Samsung is currently marketing a phone that uses iris recognition, while the iPhone has been using fingerprint ID for years now. But for Robinson, biometric authentication is one thing, and RFID microchipping is another. “The difference is technology like this is intrusive in the body. That’s quite a leap from having a Fitbit that you can take off. It’s that permanency of having something on you that could go wrong.”

From a regulatory perspective, the right to privacy has to be paramount, he adds. “Presumably, the chips are gathering data, but where will this data be stored or used. In the UK, there is specific legislation around who owns data. There’s also the potential of having data breaches.” Robinson says that it’ll be a long time before the right regulations come into place. It’s always been the case that the law is playing catch-up to technology, he adds. “Unfortunately, the law reacts to changes in technology, often led by something going wrong. It usually depends on the government identifying an issue to be resolved, such as privacy laws, anti cyber-bullying, and so on. This is untested technology in an untested legal regime. For me, I’m not sure the benefits of having it outweigh the negatives.”