There was a time when fast-growing successful businesses in the UK would have been actively courted by banks looking to get behind them.

Nowadays even those in the fortunate position of moving in the right direction are finding it increasingly hard to secure additional finance, at least on terms which do not leave them hamstrung for the next five years.

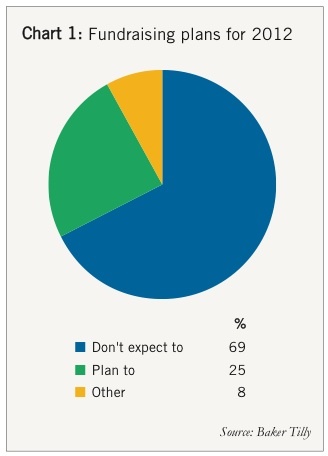

Research from accountancy firm Baker Tilly conducted last autumn suggests that 25 per cent of UK SMEs expected to raise additional finance in 2012 (see chart 1). Of those, 37 per cent planned to do this through traditional bank lending, still the favoured route despite the tide of anti-bank feeling and the pessimism among many businesses about their chances of securing funding.

Looking further into the breakdown, asset-based lending (25 per cent) emerges as the second most preferred route, ahead of other options including private equity or venture capital, borrowing from friends and family and a rights issue to existing shareholders.

The lending mechanism is nothing new, dating back at least six centuries. It allows businesses to borrow against assets or invoices, often plugging a gap during a quiet point of the financial year.

Steve Merchant, head of asset-based lending at Baker Tilly, says that in the UK’s current regulatory environment the lending system ‘ticks all the boxes’. That’s because banks don’t have to hold as much capital against an asset-based loan under the Basel III regulations as they would against an unsecured advance.

Basel III has helped accelerate the industry’s growth, with total advances up to £15.8 billion last year from £14.8 billion in 2010. Merchant highlights the moves by the likes of Wells Fargo and Santander into the ABL market as a sign that figures are likely to continue to swell over the next few years.

Funding odyssey

For Freddie Ossberg the decision to use ABL was the culmination of a hunt for funding that took him from the traditional high street banks to venture capitalists, private equity houses and angel networks.

Ossberg’s business, Raconteur Media, had reached an impasse because of a conflict with his business partner, Henrik Kanekrans. He decided the only way to move the company forward was through a partnership buy-out.

The East London-based business is a special interest publisher which produces special reports for newspapers such as the Times and Sunday Times. Ossberg and Kanekrans had bootstrapped the business, which was launched on the day Lehman Brothers imploded, using £40,000 of personal savings. However, it was stalling at a turnover of £2.5 million and profits of a few hundred thousand pounds.

Ossberg is frank in his admission that he could not afford to buy his partner out himself. But in his quest to find a backer he discovered that the majority of MBOs in post-recessionary times, which had previously been serviced by traditional bank debt, are now being done using ABL.

In the end Ossberg decided to pair with ABN AMRO Commercial Finance, previously Venture Finance, and secured a £550,000 invoice discounting facility to buy out the business as well as a £200,000 enterprise finance guarantee (EFG) loan to tide the company over a traditionally quiet time of year.

‘Had it not been that ABN AMRO offered me a £200,000 bolt-on EFG facility then I think I wouldn’t have been able to use the invoice discounting because the hole in cash would have been too significant,’ he adds.

The biggest complication, he says, was working through the exact mechanics of the process. Having not used it before Ossberg had to spend a lot of time learning the ropes and coming up with a ‘smarter’ way of financial reporting.

Dab hand

When it came to securing a new line of capital for fire equipment manufacturer and retailer Rapidrop, it was a case of moving from one ABL provider to another.

Managing director Daniel Gill says that the business had been with GE Capital for a number of years but the finance provider was becoming a ‘very difficult company to deal with’.

‘They were very hard to get hold of, and a number of staff left to start a new company,’ Gill explains. ‘We thought GE were beginning to grind into the ground slowly – every time we needed a decision about something we went from here to Paris, Paris to the States, and it seemed like it was taking forever.’

The new finance provider set up by ex-GE staff was exactly where Gill and Rapidrop ended up. They agreed a new £3 million invoice discounting facility in March, which provides the Peterborough-based business with a fresh injection of working capital.

In contrast to Ossberg, Gill has used ABL for a number of years, and in a variety of countries, and explains his preference for it. ‘It is a lot more flexible; it grows and contracts when your business moves. You have far less interference from banks which tend not to understand how a business works.’

Its quest to secure a new deal led Rapidrop into negotiations with high street providers such as HSBC and Barclays, but Gill says that he prefers to separate retail banking from borrowing and was drawn to Centric Commercial Finance because it was made up of individuals he had known for 20 years.

The company’s new line of funding was important, Gill says, because it had outgrown its cash allowance. ‘We could sit back and take a couple of years’ rest and recoup the profits, but we have always been on an expansion programme and that is really why we require extra financing.’

A lack of understanding about the lending system is the reason that Gill believes many businesses are put off ABL.

‘The trouble is that people only see the bottom end of it which is straightforward invoice discounting, very different from confidential asset-based lending,’ he adds.

‘The other problem in Britain is that we think financing is special and it really is just one of the basic elements businesses need to run. Borrowing money is like having a sub-contractor, it is part of the business and should be constantly reviewed.’

Gill believes the natural aversion of many business owners to borrowing money means that it is treated as a last resort, and they will only go to a lender cap in hand when the business is already stretched.

On the up

Although growth in ABL cash advances has been steady and sustained, the same cannot be said of the total number of businesses using the funding. This has fallen from over 43,500 in 2009, to roughly 41,500 in each of the following two years.

However, the more significant trend is the shift in the profile of companies using the funding. Whereas in 2009, 38 per cent of ABL borrowers had sales of under £500,000, this proportion had dropped to 34 per cent in 2011. Meanwhile, those with sales of over £50 million now account for 14 per cent of all companies using ABL, compared to 11 per cent in 2009.

Changing client base

Kate Sharp, CEO of industry body the Asset Based Finance Association (ABFA) concedes that client numbers are lower than she would like to see. She interprets the drop in smaller companies using ABL facilities as an indication that some are simply going out of business – rather than a sign that lenders are de-risking by turning their backs on the small fry.

Like Baker Tilly’s Merchant, Sharp believes that regulation is beginning to have an impact on how banks are lending, with many more comfortable to advance money against invoices and assets.

However, she adds that companies may not be as confident to borrow as providers are to lend. By the end of 2011, £23.1 billion was available to UK businesses through ABL facilities, but only £15.8 billion, roughly two-thirds of it, was drawn down.

There are two possible interpretations of this. The optimistic one is that businesses have adequate funding and are not forced to push their borrowing to the limits. But Sharp leans towards the other view, that companies still spooked by the recessionary environment lack the confidence to change into fifth gear.

‘It’s actually a comment about whether they are confident to invest more money and stretch their facilities. It’s a less positive picture than we would like to see.’

One company with no lack of ambition to expand is FT Solutions, a Hertfordshire-based print and brand management business.

The company was originally acquired by Tom Gurd and Peter Mahoney through a management buy-out in 1997. However, like Gill, the duo became disillusioned with FT’s backer and decided to try a different financing option.

‘The problem was that we got into bed with 3i [a private equity firm] just as the dotcom boom was bubbling up. Then it all went horribly wrong,’ Gurd recalls.

‘Within a year of doing the deal they closed the local office and all direct lines of the relationship were out of the window.’

The involvement with 3i ended in 2004 when the two did not see eye-to-eye about a potential acquisition. The business’s management bought out the private equity firm and moved to NatWest before eventually settling at Barclays.

A separate acquisition in 2009, when Barclays took the view that FT Solutions was paying too much, proved to be the undoing of the new partnership. It became apparent that the business needed a backer who was better attuned to its needs and appreciated its appetite for expansion.

Acid test

While Gurd is happy with the new £4 million deal that has been closed with Aldermore, he says the real test will come when the £25 million turnover company wants to make another acquisition.

‘If I am just trading then they get their pound of flesh. But if I go to them and say I want to buy another business and need more, then that will be the telling point,’ says Gurd.

‘Barclays were reasonably happy but then took a different view when we wanted to buy someone. Whether that would be the case with Aldermore, I don’t know.’

With the market still very uncertain, Gurd believes that acquisitions are spooking lenders. The days when M&A was regarded by finance providers as a natural aspiration for all ambitious companies are gone.

The real test for the ABL industry will be whether its risk tolerance matches entrepreneurs’ appetite for expansion, or whether it will leave as much of that risk behind as possible as it enters the mainstream.