There comes a stage in the growth of any business when the easy routes of financing have been exhausted and a serious injection of capital is needed to push the company into new areas. An institutional fundraising offers the potential for cash to be pumped into the company while acquiring industry expertise and streetwise investors.

Having guided his business through a £2 million Series A funding round with Octopus Investments in February, Artesian Solutions CEO Andrew Yates says the difference between this process and the business’s initial seed round was ‘like night and day’.

After spending 20 years of his career at enterprise software companies, including Cognos, Misys and Eyretel, Yates signed off on an $8 million (£5 million) sale of his own venture, Then Solutions, with co-founder Chris Sykes in 2004, giving him the clean slate he needed to set up Artesian.

‘I get my kicks from starting things up and getting them to a point when HR comes in. That’s when I know it’s time for me to do something else,’ he says.

With his previous business having been entirely self-funded, Yates says that Artesian, which provides brand-monitoring software, needed institutional capital to speed its entry into the market. ‘We got to a point with this business where we could see a market opportunity and we were being told by our customers that what we had was unique, but the prospect was too big to service through an organic boot-strapped model.’

Yates describes the seed round he completed with Artesian as very much an ‘informal process’, which was largely based on a letter of agreement and some ‘fancy tax planning’ put together by his fellow board member.

Unplanned upheaval

In contrast, the process of securing Series A capital was one that took Artesian through a lot of ‘painful and disruptive’ due diligence with potential investors, which Yates sums up as ‘spending days locked in a room, with the end result being sub-optimal’.

‘I think it is important, very early in the process, to find out what the investor wants,’ he remarks. ‘We were warned about one VC in particular. But it’s like there’s a girl standing at the bar and your friend is saying don’t do it, but you still go for it.’

With Octopus, however, due diligence was the beginning of a beautiful friendship. ‘It was really beneficial,’ Yates recalls. ‘We used it as an opportunity to test all of the assumptions we had, and we’ve now got financial models that are stress-tested.’

The interests of initial seed investors also need careful consideration, he says. ‘You should always invite them to participate in the round so that they don’t get diluted.’ They should get involved in meetings with VCs, he adds, so that potential backers can grill them on why they invested.

There were 80 first-round fundraisings completed in the UK during 2011, raising a total of £112.25 million for deals with known values. The average transaction size stands at £1.97 million, according to specialist research firm UKFunders (see table below). This year may be even more fruitful, as some impressive deals have been done already, including the $17 million raised for taxi app developer Hailo.

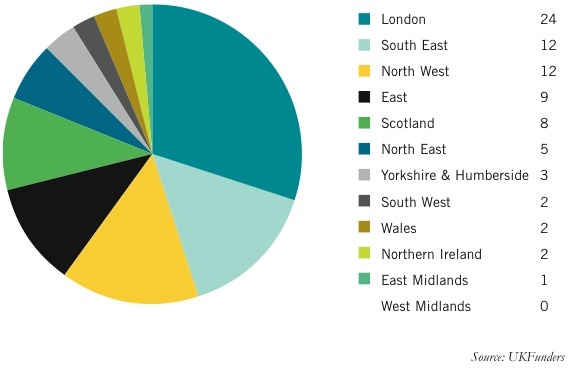

Rather unsurprisingly, London and the South East dominated fundraising activity last year, with 36 deals closed (see pie chart below). Businesses in the North West accounted for 12 first-round fundings, with investors such as the North West Fund specifically targeting businesses in the area through capital injections of between £500,000 and £2 million.

The benefit of being a VC-backed company is clear to see, with results from Experian showing that total reported gross profit for 2011 was £970 million, a 150 per cent rise from four years ago. Over a similar period, companies without venture backing saw only a 25 per cent rise.

Team, technology, traction

Ben Holmes, partner at technology and life sciences-oriented firm Index Ventures, says that the main distinction between a seed investment and a venture round is that at the latter stage there needs to be a product or service that has already had some kind of exposure to a customer base.

‘There should be some initial traction with the business model. It doesn’t need to have material revenues, but it does need to have a path and a vision that is going to make money in the future,’ Holmes explains.

Holmes highlights what he describes as the three Ts: team, technology and traction. To win backing, a business needs to demonstrate that it has a team with a disruptive vision capable of execution, a technology that can at least be shown to investors and traction in the form of a strong or growing response from consumers.

Above all, would-be investees must avoid bragging, or ‘over-representation’ as he puts it. ‘Its like there’s a girl standing at the bar and your friend is saying don’t do it, but you still go for it’

‘You need to be open and explicit about what you have achieved, and what you haven’t,’ he explains. ‘Entrepreneurs will often try and represent that they have a B+ across the board, a fairly interesting product and some traction. But I often find that it is more compelling if they are exceptionally strong on one axis and less so on the others.’

Blank canvas

For Steve Franklin, CEO of Evgen, traction wasn’t a consideration when the business received its seed investment. The company didn’t even know what it was going to do.

Based on his prior experience commercialising intellectual property (IP) in the life sciences sector, Franklin was given an initial £100,000 in seed to go off and find IP to bring to the business. His search eventually led him to a pharmaceutical composition, sulforaphane, with potential applications in the prevention and treatment of prostate cancer, as well as other forms of the disease.

Although Franklin had received funding from people who trusted him, he says attracting the interest of unknown backers was hard work. His strategy was to surround himself with other credible individuals until the business reached a ‘chugging point’ at which it started to look like a more respectable venture.

‘The challenge is that you don’t have the resources to acquire a team, so you have to get people on a contingent basis, and try to keep them on while bringing in the money,’ he explains.

From a personal perspective, Franklin says it’s important to get as much external advice as possible on business strategy before going to institutions. ‘It is very dangerous to get locked into that tunnel without conversing with the outside world,’ he counsels.

First-round fundraisings - UK

| Period | No. of deals | No. of deals with known amount | Total amount (£m) | Average deal (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 2011 | 20 | 14 | 20.87 | 1.49 |

| Q2 2011 | 15 | 11 | 17.01 | 1.55 |

| Q3 2011 | 27 | 19 | 45.74 | 2.41 |

| Q4 2011 | 18 | 13 | 28.64 | 2.20 |

| Year | 80 | 57 | 112.25 | 1.97 |

Risk and reward

Evgen closed its £1.1 million Series A round in September last year. Most of its support came from the North West Fund for Biomedical, an EU-backed fund that can afford to take a risk where there is good long-term potential, Franklin reveals. Its support helped attract other investors, and he now feels confident that it will be easier to raise institutional capital in future.

Putting together a business plan to pique the interest of potential investors is all about keeping it brief and to the point, Franklin states. ‘You don’t want to put in everything you know, which would be hard for them to get their heads around, but you need to tell them enough. They often have a pile of business plans that is six feet high.’

If a VC likes a prospect and ‘bites’, that is the time to provide more information, Franklin recommends.

Think short term first

Holmes also has clear ideas on what makes a good business plan, or a bad one. One thing that arouses his suspicion is talk about raising money in the future, or suggestions of potential valuations for a company at various future points. Instead, he recommends that companies focus on the next round, understand what sort of runway it gives the business, and explain how the management team will go about achieving its near-term goals.

There is no archetype for a good business plan, he adds; some of the most successful entrepreneurs he has seen in the past decade have been those embarking on their first venture, with no experience of pitching to VCs. The main thing that Holmes fervently recommends is an ongoing dialogue with potential investors – one that has been established from an early stage.

One such first-time entrepreneur is David Newns, co-founder of CN Creative. His venture is aiming to take advantage of an upsurge in the use of electronic cigarettes on the back of 600,000 UK internet searches a month for aids to quit smoking.

‘We used due diligence as an opportunity to test all of our assumptions, and now our financial models are stress-tested’

Alongside his co-founder, Chris Lord, Newns found the product he wanted to market after Lord successfully used it to break the habit himself. The business was spun out of the University of Manchester’s bioscience incubator, an institution that has been pivotal in providing advice and support, Newns says. ‘The idea of raising money from VCs was new to us. It really was handholding – [the incubator] put in a good nine months of work.’

Maiden success

For rookie entrepreneur Newns, the key to his fundraising success, which is based on an initial £1 million from Advent Venture Partners and a subsequent £1 million upon UK licence submission, is based on a simple principle. When pitching, the vision you have should be the one you are selling – clarity of concept is essential.

Newns pitched to eight different sources and had some ‘serious offers’. It helped, he says, that his business was revenue-generating, a fairly unusual prospect in the life sciences sector.

After seeking advice from a number of individuals who had been through the process before, and taking on the help of specialist venture capital advice service Epiphany Capital, Newns says CN Creative chose Advent because of its respectable position in the life science sector and understanding of the regulatory framework in Europe.

First-round fundraisings by region (number of deals)

Stellar cast

Unlike Newns, Azeem Azhar, CEO of social media services business PeerIndex, led a £1.9 million first-round fundraising in March on the back of a career spent operating in the arena.

The process attracted a stellar cast of institutional investors including Antrak Capital and Anthemis Group, as well as a host of angel backers such as Tom Glocer, former CEO of Thomson Reuters, Stephen Klein, previously CEO of ActiveBuddy, and Restoration Partners chairman Ken Olisa.

Azhar says that between the business’s initial £200,000 start-up funding in 2009 and its first grown-up institutional round, the focus was on getting the technology off the drawing board.

PeerIndex provides a platform that allows companies to reach social media ‘influencers’. The software identifies individuals who will spread ‘positive and impactful’ word-of-mouth messages about appropriate products. Customers include Penguin Books and O2.

For Azhar, raising venture capital is about interaction and interest, with investors wanting to see that milestones have been reached. ‘You have to get to a point where the business is very fundable, and the milestones are about proving revenue,’ he adds.

Although Azhar is no stranger to dealing with VCs, and is an angel investor himself, he admits fundraising for PeerIndex has been a ‘voyage of discovery’. Making profitability projections has been difficult, and it has been a case of drawing on the experience of the venture capital contacts he has built up over the past 15 years.

In Azhar’s view, angels are only really funding the next milestone, while venture capital firms remain much more engaged for the duration of the investment and really ‘grind down’ on the details.

If that sounds scary, it shouldn’t, according to Index’s Holmes. A sustained and robust dialogue between investor and investee can be beneficial for both, especially when it comes to a second round of funding.

‘If a backer can track progress and challenges that have been overcome, then the business will be much more comfortable when it comes to raising money,’ he advises.