A woman wearing a hijab. A man with a turban. A recent graduate wearing a crucifix. An older man wearing a yarmulke. All of these people will need to leave their religious garb at the door when getting to work, according to a new ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). GrowthBusiness speaks to leading UK legal experts to separate fact from hype.

The CJEU ruling comes off the back of the conjoined cases of Bougnaoui v Micropole Univers and Achbita and others v G4S Security Systems, two cases that deal with Muslim women who have refused to remove their hijabs at work.

Today, the CJEU ruled that prohibiting employees from wearing outward signs of political, philosophical or religious beliefs will not be deemed discriminatory under the EU Employment Equality Directive. However, this is only subject to the provision that workplaces are objectively against showcasing political, philosophical and religious symbols for the sake of neutrality, rather than that based on stereotypes or prejudices against any particular religion.

In the UK, Eweida and others v United Kingdom was a case where the UK was held to have failed to protect Ms Eweida’s right to wear a discrete cross outside her uniform. While neutral dress codes may have been given the all clear, there is still the possibility that individuals will rely on that landmark case to bring a claim that their employer has interfered with their right to manifest their religious beliefs.

Bougnaoui v Micropole Univers

A design engineer, Bougnoui, was sent by her employer to clients. A customer complained that the veil she wore “embarrassed” a number of its employees, and asked that this did not happen again. Bougnaoui’s employer discussed this with her and asked her to observe a principle of “neutrality” in relation to her dress when dealing with clients. She refused and, as a result, was dismissed.

Achbita v G4S Security Systems

Achbita, a Muslim receptionist who was contracted out to work for a third party informed her employer, G4S, that she was going to begin wearing a headscarf in the workplace. G4S informed her that the wearing of any visible symbols was contrary to its “strict neutrality” rule in the workplace. The receptionist was dismissed as a result of her refusal to go to work without a headscarf.

Interestingly, the Advocate General Opinions in these two cases reached conflicting conclusions, causing employers confusion as to whether neutral dress codes were lawful or not.

https://growthbusiness.co.uk/name-bias-corporate-britain-adam-likely-get-hired-mohamed-2549590/

In the Bougnaoui case, the Advocate General believes that while the employer was acting in its best interest, it was difficult to see how the employer’s prohibition could be regarded as proportionate. However, in the case of Achibita, the CJEU sees G4S’s blanket policy as legitimate, as it prohibits all employees from wearing outward signs of political, philosophical or religious belief, which would not constitute direct discrimination under the EU Employment Equality Directive.

Avoiding discrimination

“Employers will be reassured that neutral dress code policies will be lawful, provided that any ban on political, philosophical and religious symbols worn in the workplace is based on a general company rule, rather than on stereotypes or prejudices. However, an individual’s right to manifest their religious beliefs under the European Convention on Human Rights should also be taken into account,” says Nicola Ihnatowicz, employment partner at law firm Trowers & Hamlins LLP.

As a matter of good practice employers should ensure that they avoid dress codes that restrict an employee’s right to wear things associated with their religious beliefs, Ihnatowicz says. “If there is a prohibition within a dress code then it will be up to employers to ensure that the balance between the reason for the prohibition and the disadvantage to the employee is properly considered.”

According to Thomson Snell & Passmore’s Susanna Rynehart, this issue won’t be going away any time soon. “The ECJ said that whilst such a dress policy may still be indirectly discriminatory, it could be defended if an employer can demonstrate that the reason for the dress policy is to project a completely neutral image to its customers. This decision is however unlikely to stop further claims because the religious observance through wearing specific items of clothing or objects is a very real issue for people of faith and they will continue to challenge employers’ reasons for refusing this,” she explains.

The hijab under fire

For Bircham Dyson Bell’s Tim Hayes, the only way an employer’s policy can avoid being directly discriminatory is if it prohibits all religions signs, not just the hijab. “This means that dress codes that seek to ban items of clothing such as headscarves will also need to cover, for instance, the wearing of crosses. Also, this case concerned an employee in a customer-facing role and the employer’s case rested on its desire to project an image of neutrality. Employers will need to be sure that they are able to adequately justify their policy,” he says.

Related: Can employers ban hijabs in the workplace?

Alan Price, employment law director of Peninsula, believes that the reason behind a blanket ban on political, philosophical or religious manifestations through dress is also a key element when deciding whether the policy is indirectly discriminatory. “In this case, the aim of the employer to project an image of neutrality when in the company of customers was considered to be legitimate. A desire simply to project a corporate image may, on the other hand, not be considered a legitimate aim,” he explains.

The Court suggested that employers may need to look at ways to accommodate employees who still wish to wear religious items of clothing at work, for example, moving them to another role which did not involve contact with customers.

The Court was clear, however, in its message that the neutrality policy must be that of the employer itself. Relying simply upon the wishes of a customer not to come into contact with employees who wore items of religious clothing as a reason for a ban would not be sufficient to defend a claim of discrimination.

Businesses may run the risk of confusing religious garments and symbols, for employees with particular religious beliefs, which is flat-out unlawful.

Avoiding a witch hunt

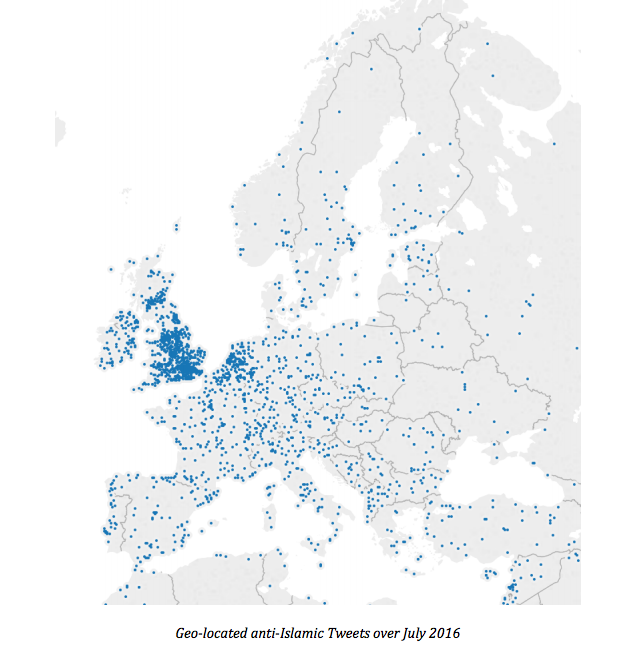

Both of these seminal cases that prompted the CJEU to make a ruling involve Muslim women, which could be misappropriated by businesses to veil Islamophobia. According to analysis carried out by the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media (CASM) at Demos, research on hateful, xenophobic, anti-disability, anti-Semitic and anti-Islamic expressions on Twitter revealed the UK’s ugly underbelly. In one month alone, the research team identified 215,247 hateful, derogatory, and anti-Islamic tweets. On average, this is 289 per hour, or 6943 per day.

Most recently, the British Islam Conference, held on the 25th and 26th of February, saw its hashtag, #BritishIslam207, getting hijacked by Islamophobic comments.

Zero-tolerance

In any office, experts advise that a zero-tolerance policy should be enforced because when people feel discriminated against they could potentially sue the employer for letting this happen. In the UK there are a list of protected categories (Equality Act 2010 [part 2, chapter 1, section 4]) which cover characteristics such as age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation so to see many of these broken on a day to day basis is unbelievable in an evolved office environment.

Meredith Hurst, partner at Thomas Mansfield believes offence of any kind in the workplace, can create a toxic and unpleasant environment, affecting staff morale and productivity. “In our experience, complaints of bullying appear to be on the increase. Employers who fail actively to deal with the perpetrators of bullying, and the underlying causes of conflict, will undoubtedly experience high staff turnover. The obligation to provide a safe and stress-free working environment may amount to an implied term of the employment contract. In extreme cases, a victim of offence in the workplace may have grounds to bring a constructive dismissal claim,” she says.

People commonly complain of ‘harassment’ without understanding its true legal meaning, says Hurst. Harassment in a legal sense must be on the basis of a protected characteristic including race, sex, disability and sexual orientation. Harassment, or more generally, ‘being picked on’ for another reason, such as for being overweight, or for having a different hair colour et cetera, may not give rise to an actionable discrimination claim, but still may cause staff to complain of bullying in the wider sense.

“Employers should focus on encouraging an inclusive workforce, regular and effective staff and management training, as well as a consistent and reasonable approach to disciplinary action. Ultimately harmonious staff relationships are reflected in a company’s bottom line and the value of tolerance should not be underestimated,” she adds.