The current gender pay gap means that women effectively stop earning relative to men on a day in November. This day is referred to as Equal Pay Day and varies according to the actual pay gap each year. In 2016, Equal Pay Day is on the 10th of November: just one day later than last year. At this rate, the gap will take another 50 years to close.

But why are so many people exploding over the gender pay gap issue, especially today?

Look up the hashtag #GenderPay and it’s a social media battlefield. From angry tweets (“Stop feeding this lie”) to conflicting arguments on LinkedIn, everyone has their own impassioned opinion on the subject.

The keyword there is “opinion”. The media is rife with the opinions of countless “expert” contributors in recruitment, financial services, technology and even the start-up ecosystem.Earlier this year, GrowthBusiness reported on the inherent biases and conflicting conclusions in scientific research on gender parity. Some studies label women as being too competitive at work and subconsciously sabotaging their peers and their own success. Conflicting research judges women for not being competitive and assertive enough, which explains away the salary issue (“you should have asked for a raise like your male counterparts”). While opinions may inherently be biased, cold hard facts are not. Yet if science too fails us, how can we benchmark progress in bridging inequality in our boardrooms?

Why #GenderPay is breaking the internet

Understandably, the hashtag #GenderPay has been virulently trending on Twitter all day (on 12 October 2016), owing to The Fawcett Society’s Gender Pay Gap Conference. With speakers from the Chartered Management Institute, Equal Power Consulting, and the Trades Union Congress (TUC), the conference has brought the issue of the wage gap right to the top.

“That means fighting against the burning injustice that … if you’re a woman you will earn less than a man”.

-PM Theresa May

Women in business, finance, recruitment and technology have taken to Twitter and LinkedIn in support of the statistics and data-led research presented a the conference, but there will always be sceptics.

“We can’t assume everyone is interested in equality. We still must appeal to the business case for it,” explains Sam Smethers, The Fawcett Society’s CEO.

If that’s the only way to make the gender pay and promotion gap an issue for our government and boards, then it’s a strong case at that. By equalising the labour force participation rates of men and women, the UK could further increase GDP per capita growth by 0.5 percentage points per year. This means a potential 10 per cent boost in GDP by 2030, according to figures from the OECD.

“Research has found that businesses with more than 10 per cent of women at the helm have higher profits than those that aren’t gender balanced. If we are to combat the gender pay gap, businesses themselves need to take a good hard look at where their pay gaps lie and how they can address them,” according to Tom Castley, VP at Xactly EMEA, a sales performance management and incentive compensation firm.

He believes that many organisations are not able to analyse pay and promotion related data properly. “With the right tools in place however, businesses can track and analyse employee performance against total compensation, to highlight where gender pay gaps in the business may lie and how they can be bridged.”

What about promotions?

A study from the Chartered Management Institute (CMI) revealed that men are 40 per cent more likely to get promoted into senior management roles. This is one of the main causes of the gender pay gap, which remains largely unchanged this year at 23.1 per cent compared to 22.8 per cent in 2015.

According to the European Commission, women are most under-represented in senior roles. Only 17 per cent of board members in the largest publicly-listed companies are women, with only 4 per cent being on boards as chairpersons and across Europe, and only a third are engineers and scientists.

But government data shows that the gap starts right at the beginning of women’s careers, leaving them to play catch-up at every level of the corporate ladder.

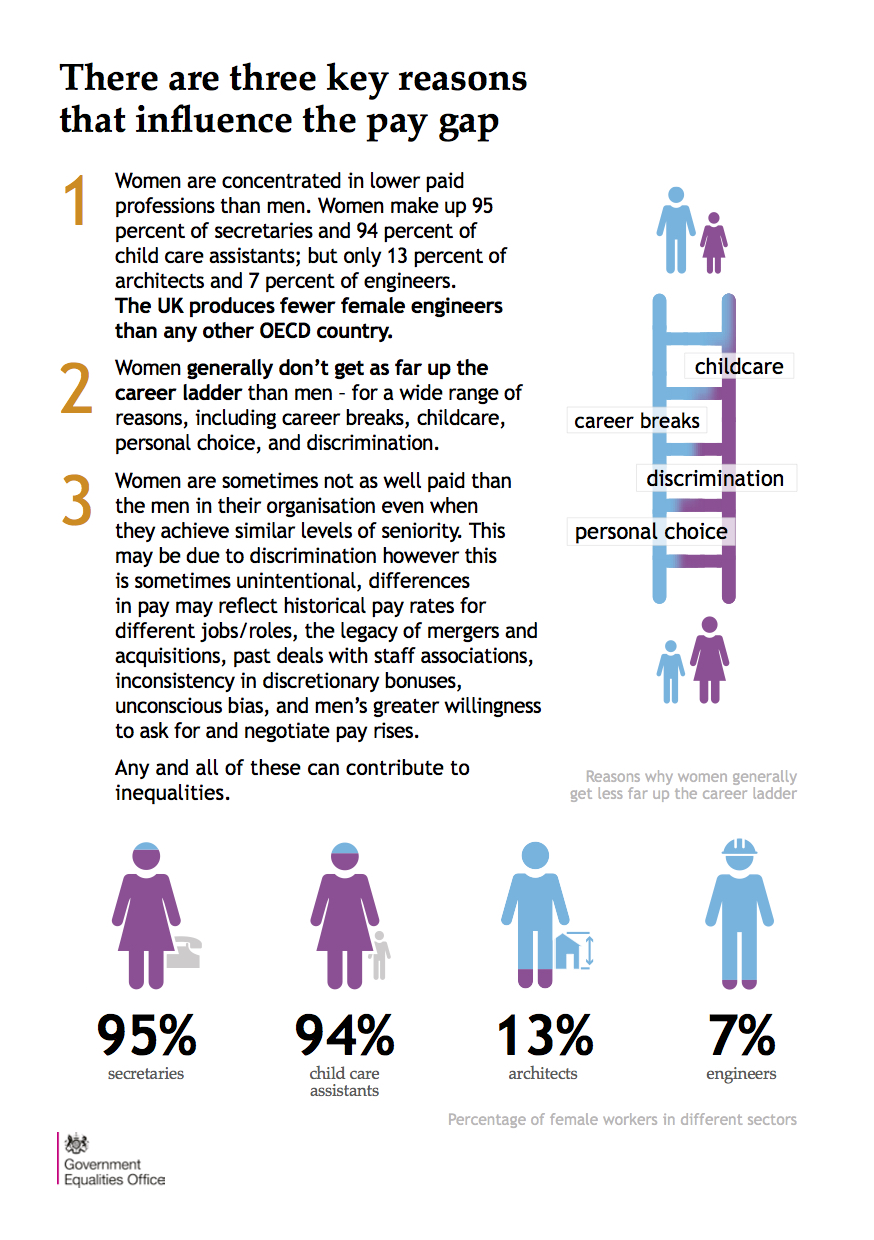

Women are concentrated in lower paid professions than men, for one. And with their careers poised to take off in the so-called “child rearing year”, issues like the high cost of childcare, and lingering domestic ideals pressure many women to opt out of the workforce, or take a pay cut to work part-time.

A Hay group study into “the real gap” analysed the income of 8.7 million people in 33 countries. It revealed that the pay gap truly sets in from maternity leave.

A similar look into data from the UK by the Institute of Fiscal Studies labelled this the “motherhood penalty,” suggesting that women are at a two-decade disadvantage when it comes to pay and promotions because of their commitments at home.

Are the figures skewed?

Part-time workers earn less than full-time workers by default. However, within the part-time workforce, gender parity is still an issue, revealing a gap of -6.5 per cent. This time, the scales are tipped against men, who are on average paid much less.

A Labour Force Survey explains that 41 per cent of women in the UK work part-time, compared to 11 per cent of men, which can potentially lower the average salary for women in the workforce as a whole.

Supporting this argument, the Office of National Statistics showed that women in the UK earn 1.1 per cent more than men between the ages of 22 and 29, and 0.2 per cent more between the ages of 30 and 39 based on an hourly rate.

How can figures revealing a pay gap coexist with figures discounting its existence? Could the proponents of the old boys’ club have actual evidence to back up their resistance to progress?

Shainaz Firfiray says no. As the assistant professor of organisation and human resource management at Warwick Business School, Dr Firfiray sees hiring and people management practices as pivotal in bridging the gender gap.

She argues that while leading companies are taking all the right steps – women are getting promoted, given top leadership roles, and provided with professional mentors and flexible work options – the pay gap continues to persist. If anything, it widens as women climb the career ladder.

“As women have closed the gap in education and experience, it is apparent that other factors such as discrimination and unconscious biases against women are more important in explaining the gender pay gap. The undervaluation of women’s work and social norms that reinforce perceptions about female economic dependence are some of the common biases faced by women while negotiating their salaries,” she says.

See also: How women can break out of the gender box when raising funds

Cultural biases are holding women back

Companies with over 250 employees will be required to report their salaries next year, which may be a step in the right direction. However, the danger is that some organisations may use metrics on pay an excuse from making broader cultural changes, which are long overdue.

Rather than just reporting what they’re paying their employees, companies may benefit more from publishing their strategy in improving gender diversity and inclusion to provide context and meaning to the salary data.

For example, are their leadership and talent management programmes gender balanced? Do they have flexible working practices? What about maternity and shared parental leave policies?

Also as employment relationships are becoming increasingly personalised with a greater emphasis on negotiable employment terms, women are facing systematic disadvantages, says Dr Firfiray.

Based on her research, she believes women rarely initiate negotiations. When they do, they routinely negotiate lower salaries and less desirable employment outcomes than their male counterparts. “This may happen because women experience self-doubt and anxiety while negotiating and also incur higher ‘social costs’ in the form of damaging their relationships with their supervisors or managers,” she argues.

“If women become dissatisfied with their pay levels and leave for other more equitable opportunities, employers may face high turnover costs and skills shortages. It is crucial that employers realise that individuals have a right to equal pay for work of equivalent value in the labour market irrespective of gender or notions of financial dependence.”

The argument circles back to the bottom line. The gender gap is a business issue that robs the economy in the most insidious way; one rooted in cultural biases and inexplicable judgments.

Bonus time: end-of-year gender blues

It’s the most wonderful time of the year, unless you’re a women in senior management. According to the CMI, bonuses for women this year in London are half the size of those awarded to their male counterparts, with men on average paid a top-up of £5,398 at the end of the financial year. Women on average receive only £2,764.

Amanda Fennell, senior director, EMEA at Xactly explains how going into 2017, it should be a priority for businesses to stamp out the gender pay gap. “Our own research found that some businesses believe women are paid less because they take time out of their careers to have children: this excuse shouldn’t stand any more,” she says.

“If we are to close the gender pay gap in the UK it is vital that we move away from the old-fashioned salary economy to the performance economy. Instead of paying people based on their position and tenure, employees must be rewarded for their output. Empirically linking pay and performance, using data, will ensure that both women and men are being rewarded fairly for what they do. Only by moving beyond the outdated gender pay gap can we secure the UK’s success for the future.”