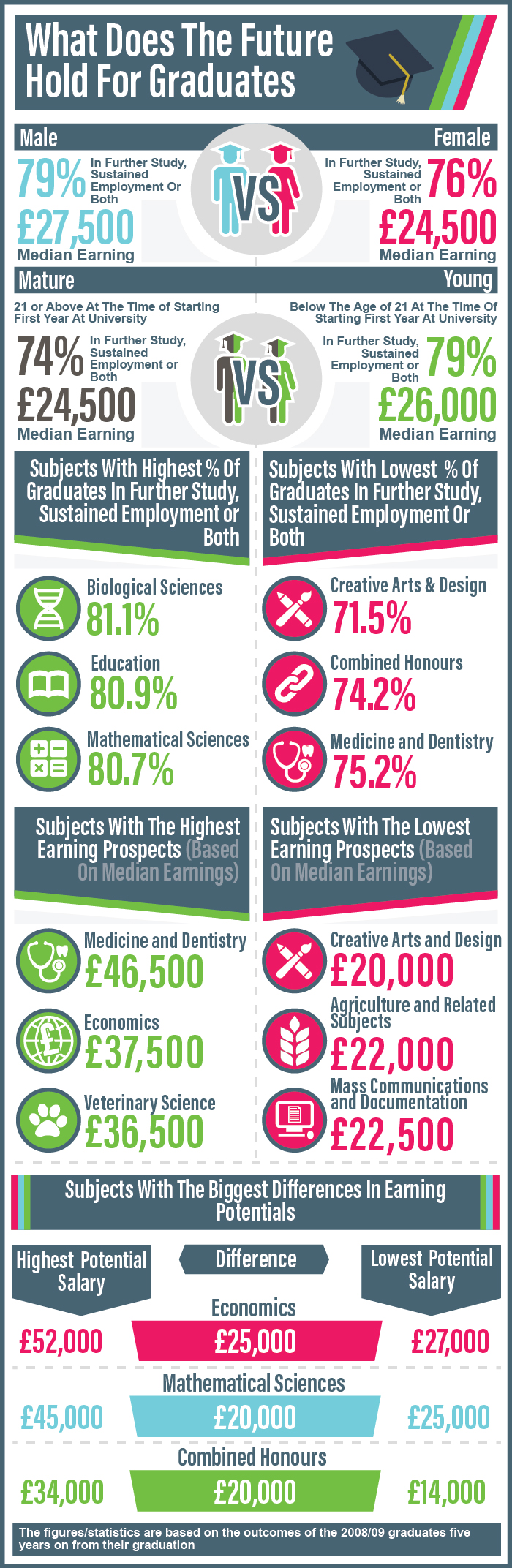

According to data from the Government’s Department for Education of how the class of 2008 is faring today, women may be making strides in the early phase of their careers, but reportedly earn £3,000 less than men based on median salary.

Five years after graduation, close to eight in ten female graduates were in further study, sustained employment or both, compared to 76 per cent of men.

Rebootonline.com analysed the report by Gov.uk to reveal that even though women fared better than men five years after graduation, the gender gap is even more pervasive than older research posits; it’s not just a mid-career thing facing women who return after a break.

But for Lusona’s Sarah McParland, it’s important to be wary of salary surveys. “There is no ‘gap’; there is no ‘great divide’ – just women working on a perfectly equal footing and, in many instances, performing at a level way above their male peers,” she says.

“I have my doubts. It’s certainly no coincidence that their findings are often headline-grabbing and startling – particularly so for those whose experiences they claim to reflect.”

According to McParland, the gender pay gap is a myth, pure and simple. There are many variables that combine to determine the salary individuals are willing to work for, she says, including the duration of their daily commute, flexible hours, and job satisfaction. “To throw gender in there as one of those variables is absurd,” she explains.

Dr Vicki Belt, assistant director of UKCES, believes otherwise. For Dr Belt, research into pay and promotions disparity is crucial to bring about real change. She believes that in spite of women’s real achievements in education, the gender pay gap stubbornly remains in more than 90 per cent of sectors in the UK, brought about primarily by occupational segregation.

“Women are under-represented in a range of sectors and occupations that offer higher paying roles – for example fewer than 10 per cent of British engineers are female. As almost a quarter of women work part-time, they are also disproportionately affected by the low quality, and poor progression opportunities offered by much part-time work,” she counters.

“It is welcome that the government is moving to bring more transparency here, by introducing a requirement for the public sector and larger firms to publish information on gender pay differences. However, there is clearly more that could be done by employers, education providers and careers advisers to create more and better opportunities for women and tackle patterns of occupational segregation.”

This infographic from Rebootonline.com examines the Gov.uk data on the future for graduates, pay gap and all.